LINKS

- Attack of the 50-Year-Old Comics

- Super-Team Family: The Lost Issues

- Mark Evanier's Blog

- Plaid Stallions

- Star Trek Fact Check

- The Suits of James Bond

- Wild About Harry (Houdini)

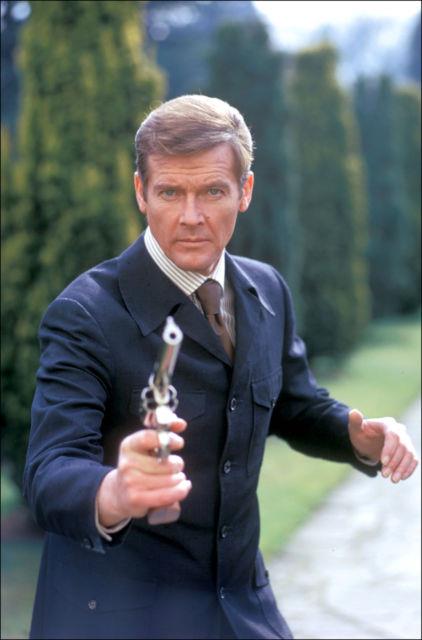

I’ve been taking the death of Roger Moore pretty hard, considering I never met the guy. But after all, he’s been a part of my life as far back as I can remember. Basically, he was who I wanted to be when I grew up.

I’ve been taking the death of Roger Moore pretty hard, considering I never met the guy. But after all, he’s been a part of my life as far back as I can remember. Basically, he was who I wanted to be when I grew up.

As an awkward, buck-toothed beanpole of a kid living in a succession of middle-of-nowhere small towns, I was completely in awe of this impossibly handsome, witty and sophisticated jet-setter who got to do the coolest things in the most wonderful places with the most interesting people in the world. Early on, I decided that was the life for me. If my off-the-rack Sears Toughskin leisure suits were no match for Roger’s bespoke creations from Cyril Castle or Douglas Hayward, and our Country Squire station wagon was a far cry from a Lotus Esprit, at least I could manage an approximation of Roger’s hairstyle, and after hours of practice in front of the mirror, raise one eyebrow at a time.

Looking back, I wonder if I could sense somehow that the “Roger Moore” I beheld was himself a construct, the invention of an insecure, pudgy and often sickly kid from working class South London who grew up idolizing screen heroes like Stewart Granger and David Niven with dreams of following in their footsteps. Young Roger George Moore taught himself to speak with a precise and measured upper-class accent and comport himself with the manners and grace of a true English gentleman, to the point where it was hard to imagine him not having been born into the peerage. No one batted an eyelash when he played a full-fledged English Lord in The Persuaders, and when he was eventually knighted in real life, it seemed a logical development. Even before I knew his biography, his carefully constructed public persona inspired my efforts to mimic the traits I most admired: an unflappable sang-froid under even the most stressful conditions, an air of class that never strayed to snobbery, pride in appearance that stopped short of vanity, the ability to weather reversals with humor and elan, to succeed by wit and wisdom where muscle was not sufficient.

Obviously, I tended to blur the lines between Roger Moore and James Bond since I knew the latter better than the former, but the great thing was that when Roger showed up on talk shows or interviews, he was a match for his fictional roles; dressed to the nines, debonair, cultured, witty and charismatic. For me, Roger Moore WAS James Bond and vice-versa. Critics would dismiss his performances as not “acting” at all, saying he was just being himself. Oddly, they seemed to be suggesting that was a bad thing. Personally, I cherished the notion that somewhere out there in the “real” world was a guy every bit as cool as he seemed on screen.

Some have complained that Roger’s version of 007 was too unflappable, too flippant about the chaos exploding around him, but for me, this was the whole point of Classic Bond, the foundation of his portrayal: Roger’s Bond wasn’t immune to fear or pain, but he worked to remain their master. His seeming indifference to danger was the key to surviving perils where indulging in panic meant courting death, and more than that was a strategy designed to drive his opponents nuts. He remained nonplussed by their efforts to intimidate him, bored with their demonstrations of strength, bemused by their grandiose speeches, because he refused to grant them the satisfaction of knowing they were getting to him.

Some have complained that Roger’s version of 007 was too unflappable, too flippant about the chaos exploding around him, but for me, this was the whole point of Classic Bond, the foundation of his portrayal: Roger’s Bond wasn’t immune to fear or pain, but he worked to remain their master. His seeming indifference to danger was the key to surviving perils where indulging in panic meant courting death, and more than that was a strategy designed to drive his opponents nuts. He remained nonplussed by their efforts to intimidate him, bored with their demonstrations of strength, bemused by their grandiose speeches, because he refused to grant them the satisfaction of knowing they were getting to him.

There are, if you look for them, plenty of moments when panic threatens to take hold, when Roger’s Bond realizes he’s in the soup and he’d better think fast: Trapped on a tiny island surrounded by hungry alligators, clinging precariously to the side of a mountain as a villain kicks away the pitons holding him up, spinning to seeming doom in an out-of-control centrifuge. In For Your Eyes Only, he’s tied to girlfriend du jour Melina as a motorboat prepares to pull them across a coral reef and tear them to shreds. “I didn’t think it would end like this,” says Melina. Looking her in the eyes, he answers calmly, “We’re not dead yet.” With only the girl to hear him, and no villains to impress, he shows what’s at his core, not flippant disinterest but the dogged determination that he WILL, he MUST survive, or that if he must die, he’ll at least not give the enemy the satisfaction of breaking him. This was old school, stiff-upper-lip English hero stuff, and I ate it up.

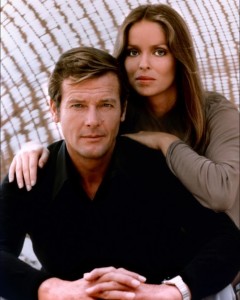

As a kid, it irritated me when adults said, “I liked him better as The Saint.” I hadn’t seen The Saint at that point, but I knew it was a TV show, so the clear implications were that (1) no matter what Roger did, Sean Connery would always be better, and (2), Roger’s talents might have been good enough for TV, but he was clearly out of his depth in movies. Eventually I did get to “meet” Simon Templar and I realized those old folks may have been on to something: I found that on the whole I liked Roger better as the Saint than I liked anyone as James Bond. Where Bond was largely amoral and professional about his job (which was, in the end, to kill people), Templar was motivated by a strong personal sense of right and wrong (if not strict adherence to the law). Bond was, for all his glamorous trappings, a glorified civil servant who had to show up at the office in the morning and take orders from a boss. Templar was a “free agent” who went where he pleased and involved himself in cases when he felt like it, and for his own reasons. That archetype of the hero motivated by a personal sense of right and wrong as opposed to patriotic duty was a better fit for Moore, more comfortable as the “knight errant” than the “blunt instrument” of a government agency.

When he transitioned from Templar to Bond, Roger brought along this sense of moral authority, the sense that he is in the game to right wrongs and deal evil-doers their just desserts. It’s not a motivation that particularly applied to Connery’s Bond, who just did what he was assigned as ruthlessly as required, not because it was “right” or “justified,” but because it was his job. It also doesn’t apply to Daniel Craig’s current take on 007, who we sense would just be out killing someone else if he wasn’t killing bad guys. More so than any of the other Bonds, Moore’s is a “crusader,” an approach that plays to Roger’s strengths as a performer even though at times it runs counter to what the character’s about. Sometimes it helps a scene, as when he kicks a killer’s car off a cliff in For Your Eyes Only (we know he deserves it) but sometimes it doesn’t, as when the script for Man With The Golden Gun has him slapping around Maud Adams; with Connery, it might have worked, but when Roger does it, he seems caddish and cowardly. Later in Golden Gun, the high-priced hitman Scaramanga compares himself to Bond and touches a nerve: “When I kill,” Roger-Bond responds icily, “it’s on the orders of Her Majesty’s government, and those I kill are themselves killers.” It’s a rare and odd moment of Bond trying to justify what he does for a living, and it’s hard to imagine Connery’s Bond offering the same defense.

Over the course of Roger’s 12-year tenure, Bond morphs to fit Moore’s screen persona as much as, or more than, Roger conforms to the Bond template, until, by the end, he’s chivalrously hanging from airplanes and blimps to rescue damsels in distress. With Roger at the wheel, the role is incrementally steered away from “ruthless assassin” to something closer to “white knight.” Fandom remains divided over whether that’s a good thing.

Alas, all good things must come to an end, and by the time of A View To A Kill in 1985, even I was ready for Roger to move on. Unfortunately, what he went on to was a series of progressively awful films until he pretty much threw in the towel on acting, but on the up side that left him free to devote his time to his charity work as a goodwill ambassador for UNICEF, championing the cause of underprivileged children around the world and becoming at last a hero in real life, as well.

Often mocked — sometimes not so gently — for being such a powerful avatar of the 70s, with its outlandish fashions, fatuous pursuits and general goofiness, over time Sir Roger became something of a national treasure in the UK. When Timothy Dalton succeeded him as Bond, many fans were eager to embrace a more serious approach to 007, and it was easy to put down Roger for the same things that had sold all those tickets just a few years before. But the further his era slips into the past, the more fondly it seems to be remembered. It’s difficult to look at where the series is today, under the often grim and intensely physical Daniel Craig, and draw a through-line to Moore’s Bond, but certain vestiges remain. If anything, his legacy is more obvious in non-Bond films like Tom Cruise’s Mission Impossible series or The Kingsman films with their over-the-top sensibilities and lack of pretension. I’d say if any franchise approximates what the Moore era was to Young Me, it’s Marvel’s superhero films, with their emphasis on dazzling spectacle, their embrace of humor, and their skill at transporting audiences to impossible but engaging worlds for a couple hours of pure, unapologetic escapism.

This has turned out to be a ridiculously long post, but like I said Roger meant a lot to me, even at a distance. I’m fast running out of childhood heroes and Roger was at the top of the list. Given the shenanigans most celebrities are prone to, it was great to have a hero who only ever went up in my estimation, never down.

In closing, I like to remember Roger in a scene from Vendetta for the Saint, one of the best stories from the series and one of two adapted for theatrical release. Near the middle of the film, Simon Templar is being manhandled by mob enforcers at the behest of a dying Mafia don, who’s just ordered his execution. The expiring villain says, “Goodbye, Simon Templar. We will never meet again.” “I know,” answers Simon, glancing heavenward with a wry smile. “I’m going that way.”

Godspeed, Sir Roger, and thanks. May your halo never droop.