LINKS

- Attack of the 50-Year-Old Comics

- Super-Team Family: The Lost Issues

- Mark Evanier's Blog

- Plaid Stallions

- Star Trek Fact Check

- The Suits of James Bond

- Wild About Harry (Houdini)

At one point I had grand plans for this blog to review whole seasons of a favorite old TV show, The Six Million Dollar Man. Ultimately, I made it as far as the pilot movie, two follow-up TV movies and the first proper episode (which was probably also the best) before the wheels came off. To a degree, this was due to the dozens of other things always vying for my time and attention, but in all honesty, there was one other important hurdle that derailed my plans.

At one point I had grand plans for this blog to review whole seasons of a favorite old TV show, The Six Million Dollar Man. Ultimately, I made it as far as the pilot movie, two follow-up TV movies and the first proper episode (which was probably also the best) before the wheels came off. To a degree, this was due to the dozens of other things always vying for my time and attention, but in all honesty, there was one other important hurdle that derailed my plans.

Turns out the show wasn’t all that great.

Don’t get me wrong; in its day, The Six Million Dollar Man was terrifically entertaining to 9-to-13-year old me, but watching it now, I’m struck by how formulaic, cheap and downright sloppy it all was.

Lots of TV shows operate on a “shoestring budget,” but TSMDM often seemed to limp along with no shoestrings at all. Universal Studios was a tightwad operation that never filmed cheaply what it could get away with not filming at all; basically any shot that couldn’t be easily captured on a studio backlot was lifted from an old film in the Universal vaults or even public domain footage from the U.S. government. If the script calls for a helicopter to fly over, why spend money renting one when you can just recycle combat footage of Huey choppers in Vietnam? Scenes of Steve running are recycled repeatedly, often showing him in a California desert whether the story is set there or not. Why? Because there was plenty of desert “running” footage already in the can from “Population Zero.”

Having recently read a couple of books detailing the painstaking process of turning a Star Trek script into a filmed episode, its amazing how little planning seems to have gone into TSMDM. You get the distinct impression the editors kept finding episodes five or ten minutes short or missing information key to understanding the plot, necessitating all sorts of editing room fakery. A scene with multiple actors in the frame will switch suddenly to a blurry close-up of a lone performer (enlarged from the original, wider shot) to cover the fact that additional dialog has been added in post-production. Or maybe that new time-killing dialog is covered by a thrilling view of vehicular traffic outside Oscar’s office building. Maybe audiences were too unsophisticated or indifferent to care about this stuff in the 70s, but in an age where everyone has their own smartphone camera and Youtube channel, its impossible not to see through such clumsy tricks.

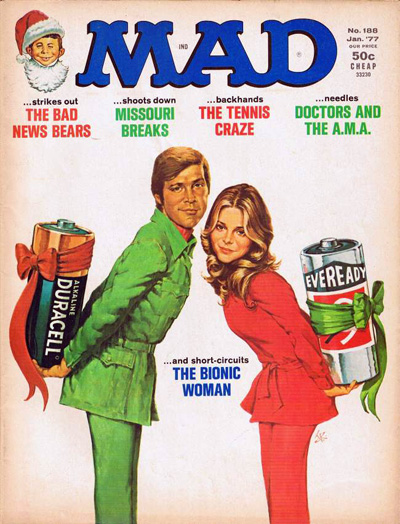

All of which brings me, in my usual roundabout way, to “The Bionic Woman,” a second-season two-parter that stands out for all kinds of reasons, not least because it’s actually well-written, tightly edited and emotionally involving. The production values are still pretty skimpy, but for once, you get the feeling some thought and planning went into things ahead of time. As slowly as plots would typically unspool on this show, you’d think a two-parter would be the last thing anyone needed, but this story keeps things moving fast enough to avoid boredom, but not too fast to keep all the characters from getting a moment in the sun.

So, the story: After a brief “mission” sequence to add some action and set up a (largely unimportant) subplot, the story finds Steve taking a rare vacation in his (previously unseen) hometown of Ojai, California. Once there, he finds another famous former resident is also visiting; his childhood sweetheart Jaime Sommers, now a celebrated professional tennis player. The two rekindle their old romance and seem headed for matrimony when a devastating skydiving accident leaves Jaime nearly dead. Calling in every favor he’s ever earned with Oscar Goldman, Steve begs his boss to authorize life-saving surgery to replace Jaime’s shattered legs, right arm and ear with bionic versions. Oscar warns Steve that if he does green-light the surgery, Jaime will be expected to serve her country in the same capacity as Steve, and he’s sure Steve won’t like it when she gets that call to duty. A desperate Steve is willing to agree to any conditions, so the surgery proceeds.

On waking, Jaime is at first horrified to find herself a “freak” of science, until Steve reveals he’s bionic, too. After that, she adjusts well and the two go forward with their wedding plans. Sure enough, however, the day comes when Oscar needs Jaime for a job, and as predicted, Steve’s not happy about it. Jaime has a mind of her own, though, and wants to go through with it, albeit with Steve along for support. Complicating matters, Jaime experiences strange side effects of her surgery, including a lack of control over her bionic arm and eventually, terrible headaches. Her debut mission is mostly successful but nearly goes very wrong when she suffers a bionic flare-up. Eventually we find that Jaime’s body is rejecting its bionic enhancements and a dangerous clot has formed in her brain (because of the ear implant), necessitating immediate surgery. Before she can get it, though, she runs off in a headache-induced panic, and Steve must chase her down in the middle of a thunderstorm. He catches her, but too late, and she dies on the operating table despite Rudy Wells’ best efforts. Steve is left alone and broken-hearted.

After nearly two years of watching our imperturbable hero knock down various straw men in simple “out of the frying pan, into the fire” action plots, this all makes for a remarkable left turn into emotion-based, character-oriented storytelling, with a surprisingly downbeat ending. Yes, there’s a “mission” to complete and a running subplot about a villain who’s out to find and kill Steve, but all that takes a back seat to the romance and tragedy of Steve and Jaime’s story. You can sense just how grateful the cast is to have something to sink their teeth into for once, and they rise to the occasion.

The scene in the hospital where Steve pleads with Oscar is particularly strong: Richard Anderson does a great job as Oscar, torn between his sympathy and affection for Steve and his weighty responsibilities as head of the OSI. Obviously he can’t just go handing out bionics to every hard-luck case that comes along: Steve was different, being an Air Force officer already sworn to serve his country and a reasonable candidate for special ops work. Jaime, however, is a tennis player and civilian; how can he justify the expense of her surgery, and if it works, how can he know she’ll have the desire, let alone the competence, to be an agent? Lee Majors also seems eager to dig into something substantial for the first time since the pilot movie. He does a great job conveying the desperation and anguish of a man who’s used to being able to handle anything, now powerless to save the woman he loves and reduced to abject begging. When Oscar tells him he’s out of his head with grief and doesn’t understand the full implications of what he’s asking, we know Oscar’s right. It’s a rare moment in a series where Steve’s judgement is usually unassailable; here, reason takes a back seat to passion. You can’t help but wish there had been a few more moments like this in the series.

This is also a moment where the story could have gone in a very different direction that might have been even more interesting, but never would have flown in 70s prime time. To wit: What if Oscar had said “no”? Surely, he’d have been within his rights, and logically it would’ve made a lot more sense than agreeing to the surgery, thus placing personal friendship above national security (let alone the federal budget). We’re cool with it because hey, it’s Steve, but objectively, isn’t Oscar in the wrong to green-light the procedure? If he had said no, and Jaime had died from her injuries, what would have happened with Steve? Would he have gone rogue? Turned against Oscar and the OSI? Would he have just sulked and continued to do his job, but not with much heart, and hating Oscar all along? Would he have sunk into a depression that made him sloppy enough to end up getting killed? Maybe all this factored into Oscar’s thinking: maybe he looked at saving Jaime as his best chance to hang on to Steve? Anyway, if he’d said no, Universal and ABC would have lost out on a hit show when Jaime returned from the dead, so I guess it worked out.

Looking back, what’s most remarkable is that such a hokey concept works as well as it does. On the face of it, this whole thing seems like the kind of bad idea only a studio “suit” could come up with: a bionic woman to go with the bionic man (Jaime herself brings up the “Bride of Frankenstein” comparison), who just happens to suffer almost exactly the same injuries suffered by Steve. The only two bionic people in the world and they just happen to be romantically linked, and from the same small town. She gets a blue jumpsuit to match his red one so they can tun around in slow motion together, sharing lovesick glances. On paper, everything about this scenario says it should have been an eye-rolling, shark-jumping moment for the series, but somehow it actually works.

A lot comes down to the casting: Lindsey Wagner is perfect here, bringing a humanity and sensitivity to Jaime that makes her tremendously endearing and sympathetic. Beautiful but in a less glamorous way than many of the women Steve dallies with through the series, she has a “girl next door” quality that fits the down-to Earth, “everyman” qualities Majors projects onto Steve. It’s entirely believable he would fall in love with this woman. When Jaime’s bionics begin to fail her, Wagner is great at wordlessly conveying her unease, making furtive attempts to hide her condition from Steve and his parents, and ultimately, we sense, coming to understand on some deep, scary level that her story is going to end very badly. Before everything goes south, she asks Steve “We’re going to have a happy ending, right?”, the foreshadowing laid on pretty thick, but not without impact. We’ve all seen enough episodes of Bonanza to know what happens to would-be brides of TV heroes, but in this case there’s a real feeling of disappointment that Jaime’s days are numbered. It’s frankly impossible to imagine another actress in this series who could’ve done as well in the role as Wagner; certainly Majors’ real-life wife Farrah Fawcett, already a two-time guest star, would’ve been in way over her impressively-coiffed head.

The other key to making this story work is the writing of Kenneth Johnson, who would go on to shepherd Jaime’s adventures in her own show as well as those of The Incredible Hulk. There’s a humanity to the proceedings that keeps us from stopping to ask questions that would make the whole thing fall apart.

And yet, there are indeed questions. For instance: Since when is bionic enhancement a “life saving” surgery? Yes, Jaime’s legs and arm are crushed beyond repair, but why would that lead to death? If the limbs are bleeding uncontrollably, wouldn’t amputation be enough to prevent fatality? If there are internal injuries threatening her life, why would prosthetic limbs change anything? In the original pilot movie, Steve endures numerous surgeries to fix his internal injuries first, then spends weeks, maybe even months as a bedridden amputee while his bionic limbs are assembled (at one point rousing from his medically induced coma long enough to realize his fate and attempt suicide!) so why, in Jaime’s case, do the prosthetics have to go on right now, at risk of death?

As far as that goes, how is Rudy Wells able to produce custom-made bionic limbs at a moment’s notice? Again, Steve’s new limbs had to be custom designed to mimic the originals perfectly, and it took a lot of time. With Jaime, Rudy just opens up a box and voila — there’s a pair of lady legs that’s just the right size and shape to fit Jaime. Does he have a storeroom at OSI full of limbs in all shapes, sizes and colors? (“Hey, quartermaster? Please send up a pair of legs for a 5-foot-7 caucasian female, size 6 shoe. Thanks.”)

This episode picks up an interesting thread from earlier in the season when we met “The Seven Million Dollar Man,” another would-be bionic ally who doesn’t work out. In the case of Barney Miller (later Hiller), the problem isn’t physical but mental; he can’t handle his new abilities and goes rogue before having to be de-powered. But the end result is the same; Steve is left the only one of his kind. The opening credits call him “The worlds first bionic man,” hinting at Steve’s role as a prototype and insinuating that in time he’ll be joined by others, but now after two dramatic failures he’s still the world’s ONLY bionic man, and Oscar Goldman’s expensive pet project has achieved only a 33% success rate. When Steve confesses to “a lot of loneliness” in the first half of “The Bionic Woman,” we can imagine he’s referring not only to his romantic status but his unique status as a bionic being.

This sense of isolation is touched on again when Steve’s mom catches him engaging in bionic horseplay with Jaime on the farm, and he has to explain how their feats are possible. Here we learn for the first time that his bionic nature has been kept secret even from his closest family members, for “security reasons” he says (although he’s quick enough to fess up once the cat’s out of the bag). This, too, is a nicely handled scene, as we see Steve and his mother talking at a distance but hear audio snippets from the “origin” sequence that opens the show: the test flight, the crash, the operation. It’s a clever and artful approach that, again, shows a polish not found in the average episode.

A welcome (and rare) moment of continuity comes in a scene between Steve and his “dad” Frank, who we learn is actually his step-dad. They even mention that it was Steve who got Frank and Steve’s mom together. This is cool as it doesn’t undo the first season episode, “The Coward,” which establishes that Steve’s birth father died in the Korean War. It would’ve been easier (and frankly, typical) to just ignore this earlier entry, so the extra effort here is appreciated.

Okay, I almost got through this whole review without acknowledging the elephant in the room: Yes, this is the episode where Lee Majors sings. And not just one song, but two. First up is a honky-tonk diddy about “cuttin’ loose” and then the supremely sappy ballad, “Sweet Jaime.” (Follow that Youtube link at your own risk). Let’s just say if “actors who think they can sing” was a medically recognized disorder, Lee Majors would be the poster boy. Not only does he have trouble staying in tune, it almost seems he doesn’t have the breath to get through the attempt. Considering it must have been his idea (has any producer ever approached an actor in a dramatic series and said, “You know what would really sell this episode? You should sing!”), he sounds like the effort is hurting him worse than that plane crash. Here we seem to have reached one of the pivotal “mile markers” in any long-running series: the moment when the star begins throwing his weight around and demanding “vanity” bits, more often than not involving singing, and usually with similar results. Yes, it does spoil the mood of an alternately sweet and tragic episode by inviting giggles; as a youngster it brought the crushing realization that my idol wasn’t so perfect, after all. But in a strange way, it kind of works if you forget it’s Lee Majors and think of it as Steve, an otherwise imperturbable (some would say wooden) paragon of male machismo exposing his heart to perform such a treacly tune in such an awkward and potentially humiliating way (“I don’t know how to sing, but baby, you make me want to try!!!!”). It certainly makes him seem more vulnerable than he’s ever been. Admittedly I might be blocking memories in self-defense, but I think this was his only stab at crooning in the series, meaning we’d have to wait until “The Fall Guy” for another fix of musical Majors magic.

On the whole — and even with the singing — this entry stands out as one of the high points of the series. Audiences agreed, with Jaime’s character proving popular enough to return from the dead in the third season opener before spinning off into a series of her own. Eventually she would become arguably a bigger deal than Steve himself as an icon of 70s TV. I kind of resented that as a kid, and after all these years I’m still fairly conflicted over whether it was a good thing to undo the end of this story. Judged on its own merits, however, the “Bionic Woman” two-parter ranks up there with the best of The Six Million Dollar Man.