LINKS

- Attack of the 50-Year-Old Comics

- Super-Team Family: The Lost Issues

- Mark Evanier's Blog

- Plaid Stallions

- Star Trek Fact Check

- The Suits of James Bond

- Wild About Harry (Houdini)

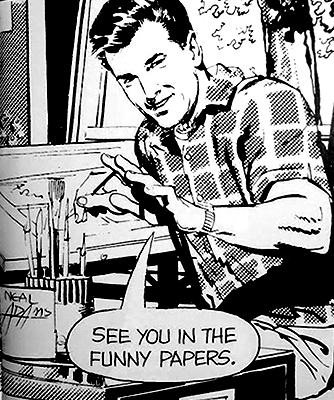

When I was a kid, I wanted to grow up to be a comic book artist. I suppose that wasn’t so unusual an aspiration for a youngster, but I was pretty specific: I wanted to be Neal Adams.

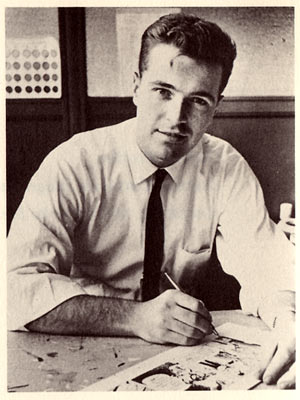

Come to think of it, maybe that part wasn’t so unusual either, at least for comic fans of my generation. Adams exploded onto the scene with a style fresh and stunning enough to be fairly labeled “revolutionary,” and a lot of us couldn’t get enough of it. In a medium by definition “cartoony” in nature, and one where constant deadlines often led to artwork that felt rushed and repetitive, Adams kept delivering super-detailed, creatively designed mini-masterpieces that literally offered new perspectives on the superhero genre. In fairness, he couldn’t crank them out any more rapidly than anyone else could — maybe less — but what he did deliver was always worth the wait.

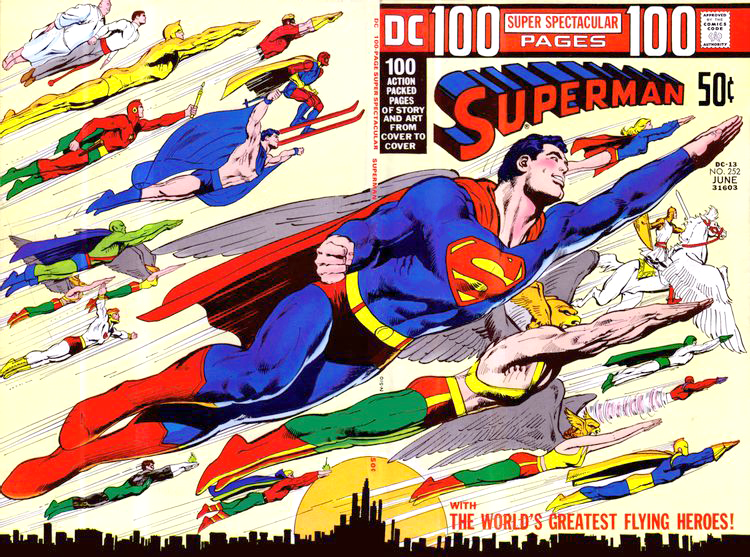

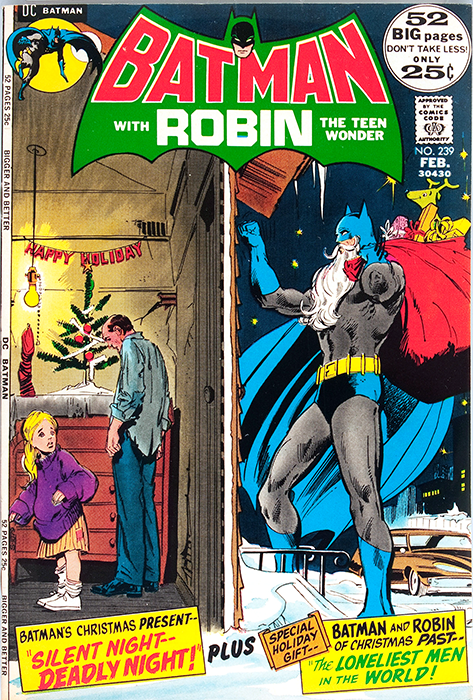

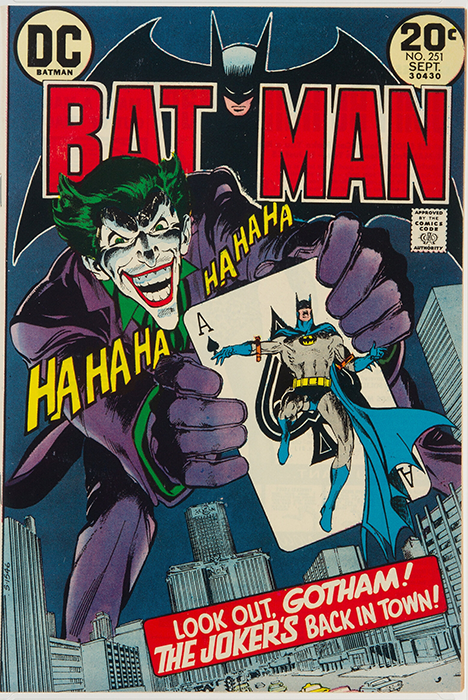

Looking back, some of the earliest comic book images to captivate me as a wee lad were drawn by Neal Adams, among them Batman #239, possibly the first comic I owned, purchased for me at a Five and Dime by my maternal grandparents and featuring Batman in a Santa beard; World’s Finest #208, with Superman (impossibly) towing the Earth behind him using chains while the delightfully odd Dr Fate cheers him on; and Batman #251, which gave us a terrifying reinvention of The Joker and presented me with the first full-length story I’d seen illustrated by Adams after all those cool covers.

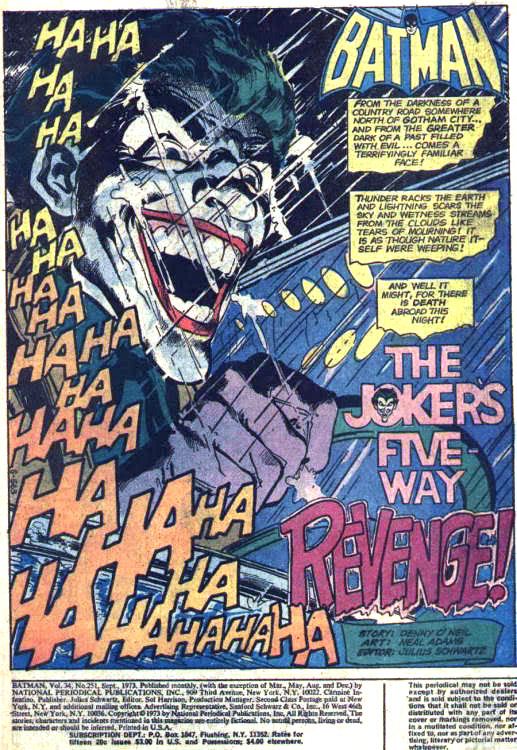

It’s likely that the credits box for that story, “The Joker’s Five-Way Revenge,” was the first time I had a name to associate with the images I’d been so drawn to: “Art: Neal Adams.” On some level I always knew that comic books didn’t just spring magically to life, growing on spinner racks like leaves on a tree. Someone somewhere had to be writing and drawing and printing these things, and yes, some stories looked better than others, but until this point it didn’t really matter to me who was making them, or how. It was always the stories that mattered, not the storytellers. Now, suddenly I was fascinated with the whole process: who was this guy Neal Adams, where was he, how did he draw this stuff, and why did I like it better than other material? And, tantalizingly, if he could learn to draw like this, then could I?

Eventually I’d be able to recognize the styles of other artists — lots of them — and I could tell you who drew what, easily. But it was Adams who first made me realize how important artists could be to a story; that they all had styles as individual as autographs; that even within the confines of being told what to draw, they could still make choices about how to tell a story through imagery, each using their personal bag of tricks in ways uniquely their own. It actually mattered who was behind that pencil or brush.

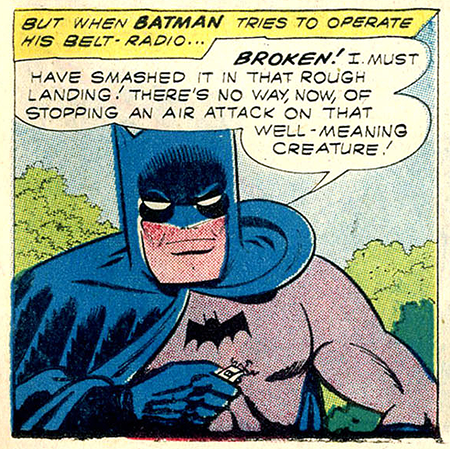

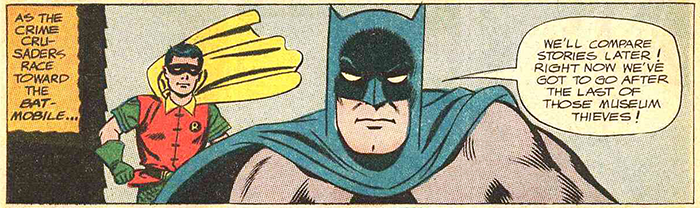

For a long time, the prevailing wisdom among comics publishers was that their readership completely turned over every 7 years, as older kids aged out of the hobby and younger ones took their place. Given that premise and looking through the “7-year” window, it’s easy to see what a game-changer Adams’ art was for my generation. Consider the way Batman looked in 1959, which is pretty much how he’d looked since the early 1940s…

Six years later, and after a much-ballyhooed launch of a “New Look” Batman, things were different but still pretty lackluster:

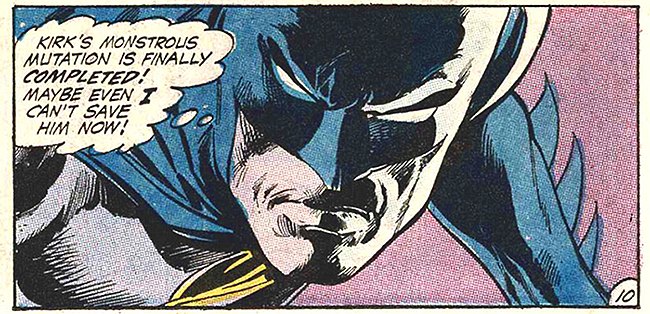

But just five years after that, with the arrival of Neal Adams, here’s where we found ourselves:

Wow.

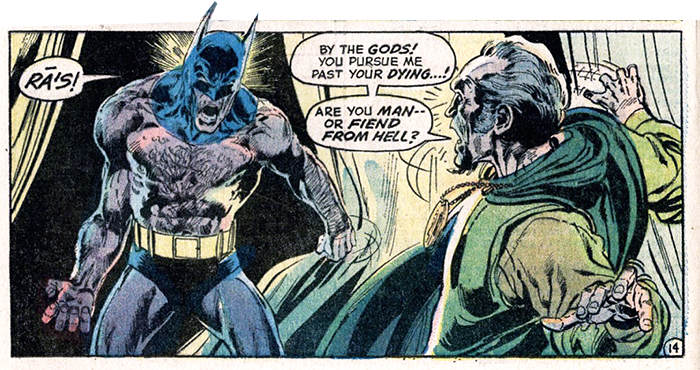

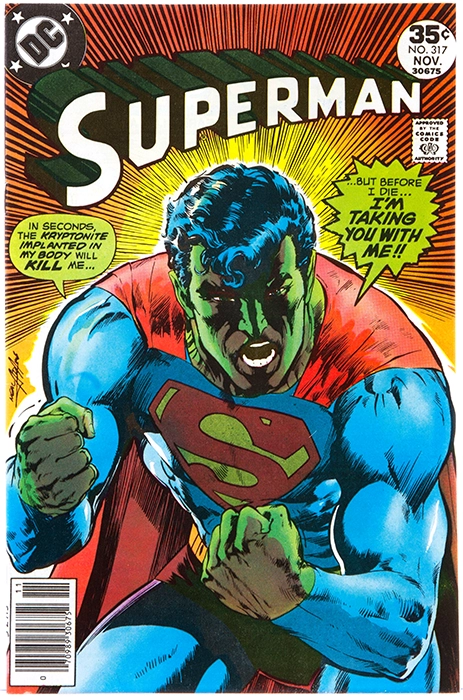

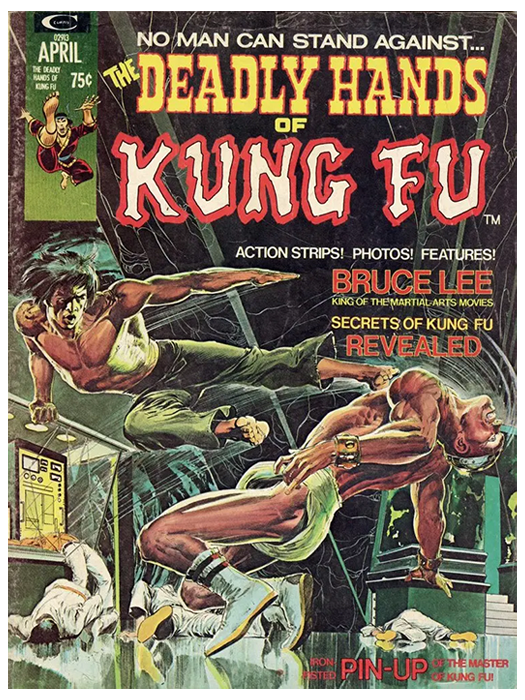

Adams brought intensity and drama to every scene he drew, employing layouts and poses that always seemed carefully thought-ought and executed for maximum impact. His mastery of anatomy and facial expressions made his characters feel like real, living beings. The term I’ve seen sometimes applied to his art is “hyper-realism” and I think it fits, mostly because of the “hyper” part. There was more to it than simply (?) drawing people and things as they are; Adams drew them as more glamorous, glossy, sexy and exciting than they could ever really be. Outside of opera or pantomime, real people probably never assumed some of the melodramatic poses Adams placed them in, or contorted their faces into such “broad” expressions as if for the benefit of theatre-goers in the back row. But exaggerated emotion is a key element of the comic book “language,” and Neal understood that. His art was too realistic to be “comic” and too over-the-top to be “photorealistic.” It occupied an alternate reality all its own, in a world cooler, more dynamic and sharply defined than ours.

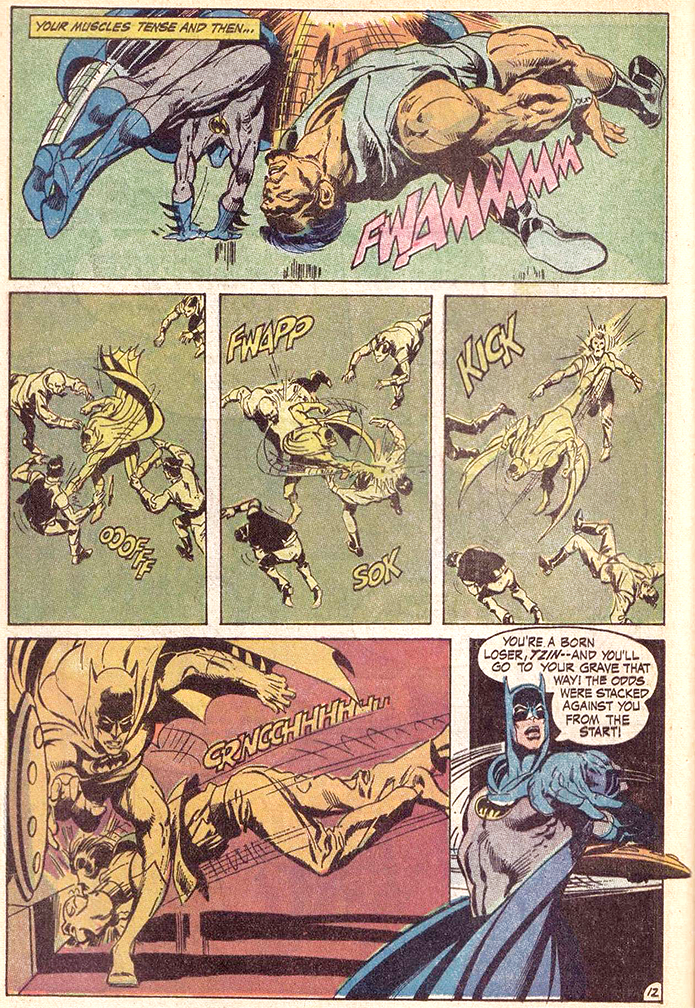

Besides anatomy, Neal was a master of visual storytelling. Consider this page-long, wordless fight scene, carefully choreographed to convey a sense of flow and pacing, like watching a film unspool on the page.

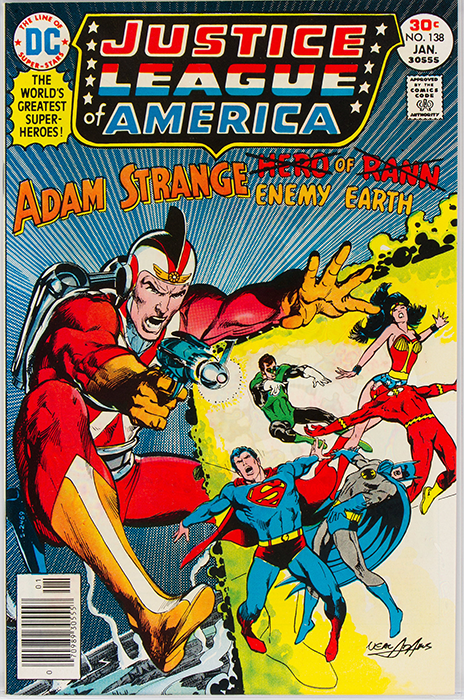

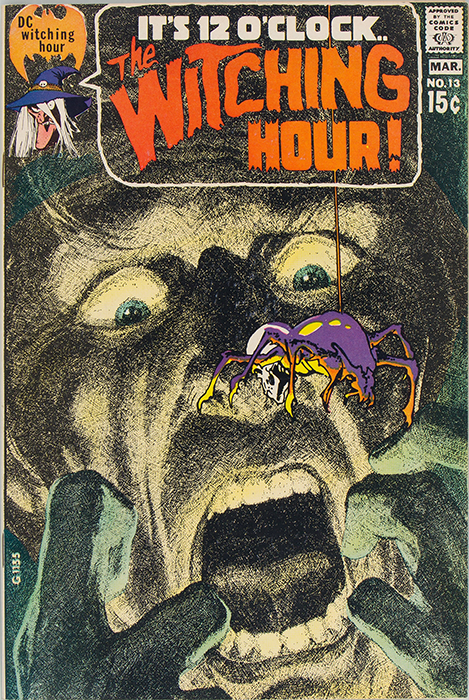

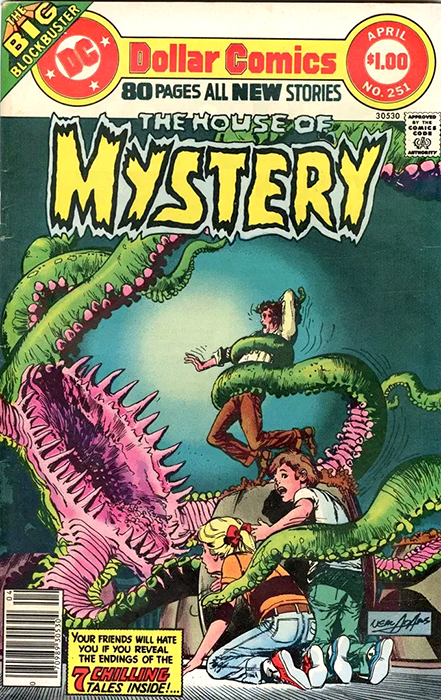

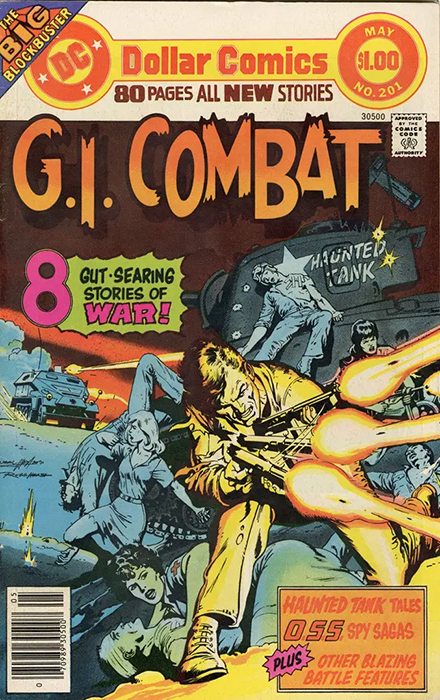

It’s also hard to think of an artist more adept at designing a cover for maximum sales appeal. I’m sure I’m wasn’t the only kid to eagerly snatch up a comic with a spectacular Neal Adams cover only to find the interiors drawn by some “lesser” artist, then after a pang of disappointment deciding to buy the thing anyway. On the other hand, when you did find an Adams-drawn story on on the inside, what a thrill! I remember lingering over each panel of each page, trying to drag out the fun like a kid rationing Easter candy to last the whole week.

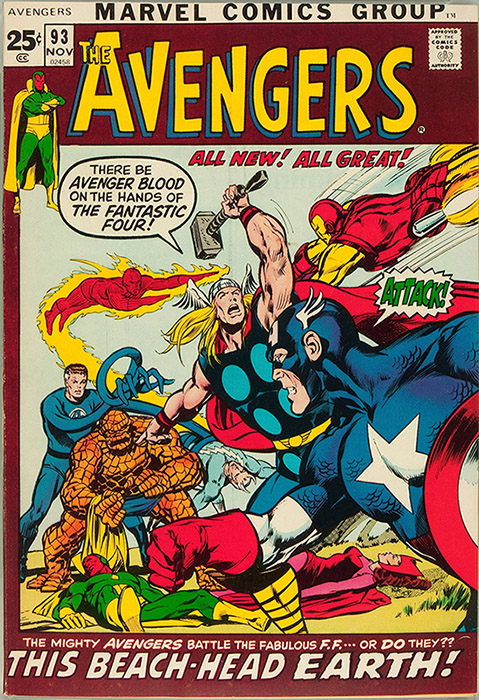

I remember being in middle school when some crazy trade or other ended up with me taking possession of two remarkable books…one was Amazing Spider-Man #122 and the other was Avengers #93. I knew that technically I should’ve been most excited about the Spidey book, featuring as it did the history-making demise of the Green Goblin, right on the heels of Gwen Stacy’s death one issue earlier. However, Avengers #93 made that look like chump change: here was a true marvel (literally) I’d never even known existed: a story not only drawn by Neal Adams but one clocking in at roughly twice the length of a normal issue. Crammed into its astonishing 52 pages were Neal’s takes on Captain America, Iron Man and Thor, plus just for good measure Captain Marvel, the Fantastic Four (sort of) and an extended sequence with a microscopic Ant Man traveling through the android body of The Vision in a tribute to Fantastic Voyage. Having this amazing artifact land in my lap from a period before my collecting days was like stumbling onto a Tiffany lamp at a yard sale. It still ranks as one of my best days as a fan.

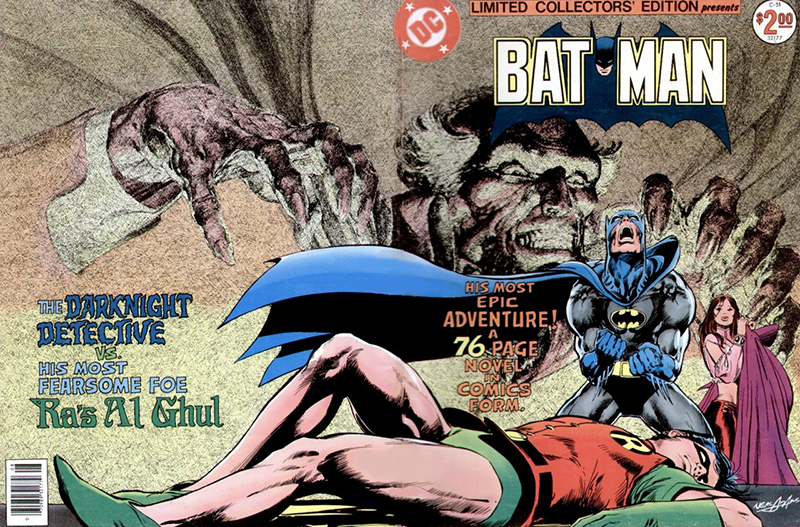

Not too long after that, I rode my 3-speed bike to the drug store for my weekly comics haul and discovered the tabloid-sized Limited Collectors Edition #51, reprinting a multi-part, epic battle between Batman and Ra’s Al Ghul, drawn (mostly) by Adams and adorned with what was surely the greatest wrap-around cover in history. I shelled out two dollars for it — quite possibly my entire comics budget for the week — asked the cashier for a bag and headed home with my treasure. Then out of nowhere appeared a particularly fearsome neighborhood scourge of a dog which gave chase, barking and growling menacingly while I pedalled my heart out. When the mutt got close enough to nip at my bag, I could swear I heard it rip, and that’s when I learned there was something I feared more than a dog attack: losing two bucks and the prettiest Neal Adams book I’d seen. I stopped the bike and yelled at the dog in a blind rage and it ran off, possibly frightened by my screamed curses but more likely terrified of catching rabies from an obviously insane comic book fanatic.

Alas, I came along at the tail end of Neal’s most prolific period in the biz, just before he abandoned comics for the more lucrative world of advertising. A lot of his greatest material I had to discover in reprint collections, but the upside was that pretty much everything he drew was an instant candidate for reprinting somewhere, sometimes barely a year or two after its first appearance. Half a century later, most of it’s still being reprinted and there’s little reason to believe that won’t continue for another 50 years to come.

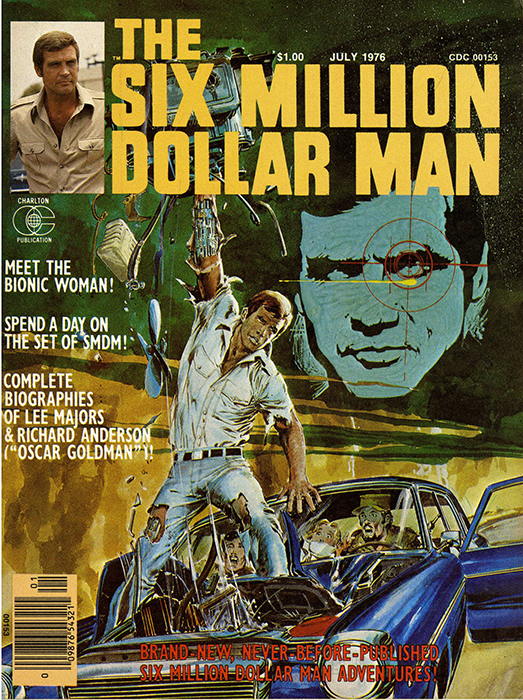

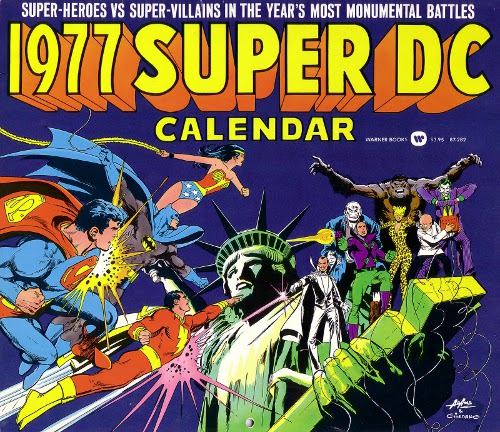

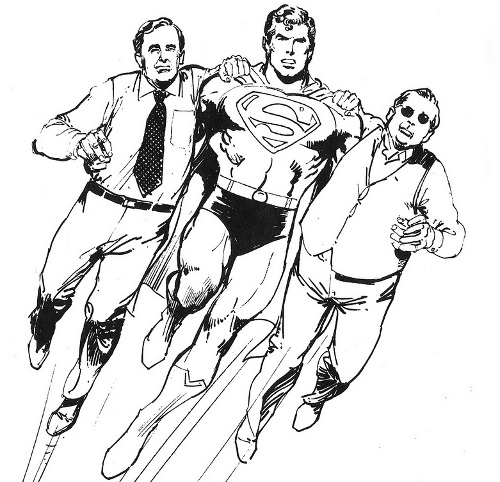

The good news was that even having moved on to the world of advertising, Neal often circled back to superheroes to provide art for toys, puzzles, t-shirts, bedsheets, posters, calendars, etc, so there was still plenty of his work to enjoy.

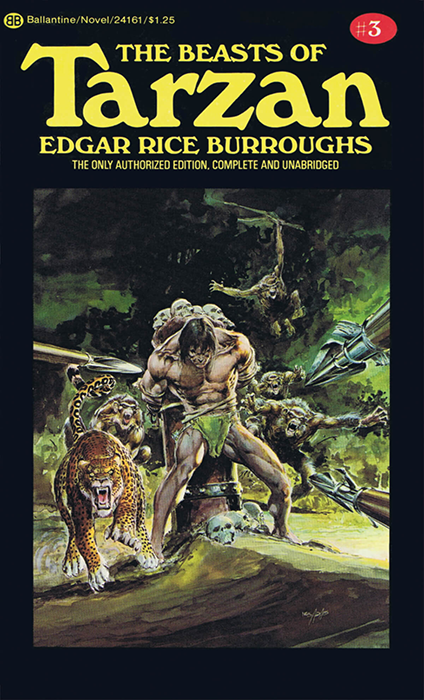

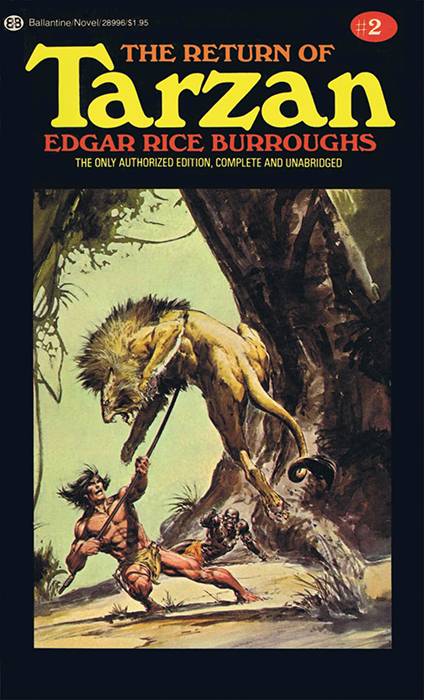

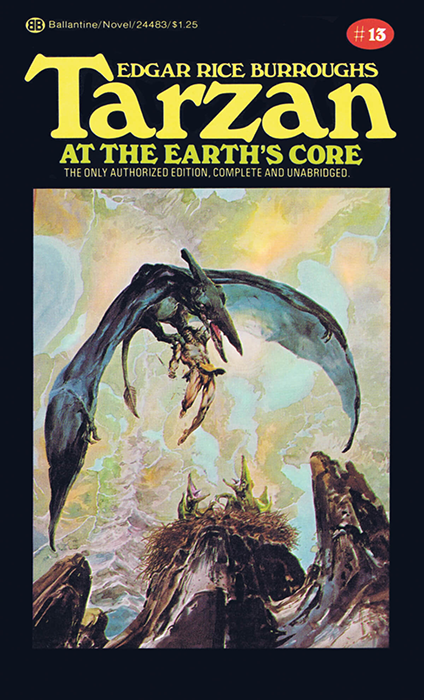

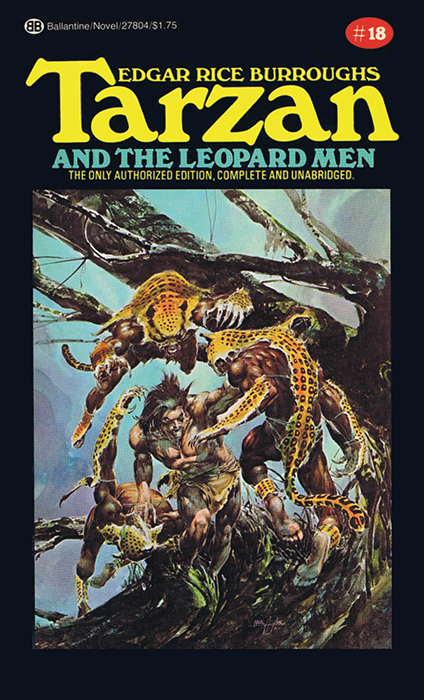

There were also his spectacular cover paintings for the 70s paperback reprints of the original Tarzan novels, which were enough to tempt even this kid who normally couldn’t see jungle adventures for dirt.

Ironically — but in retrospect not surprisingly — even though Adams brought a fresh new approach to comic art, his success inspired legions of imitators (of which, remember, I had hoped to be one), which meant that soon enough, comics started looking more alike than ever. But there was always something extra in Neal’s work, some magical element that even the most slavish imitators could never really duplicate.

From time to time, Adams would return to comics to draw a few covers, briefly launch his own line of titles and, most recently, write and draw multiple mini-series devoted to Batman, Deadman, Superman and others. In all candor, I have to admit I didn’t care as much for his later work. He transitioned to inking with a pen, which didn’t appeal, and developed new coloring techniques that turned me off. His faces and poses became even more exaggerated, awkwardly so for me. People’s teeth showed no matter what their mouths were doing, which never seemed natural or perhaps even possible. The less said about his writing the better. Eventually I reached a point I’d never have considered imaginable as a kid, where the name “Neal Adams” on a new book meant a likely “pass” for me instead of a guaranteed “buy.” I read them when I could get them for free on the “Hoopla” app and sometimes even then, I couldn’t finish them.

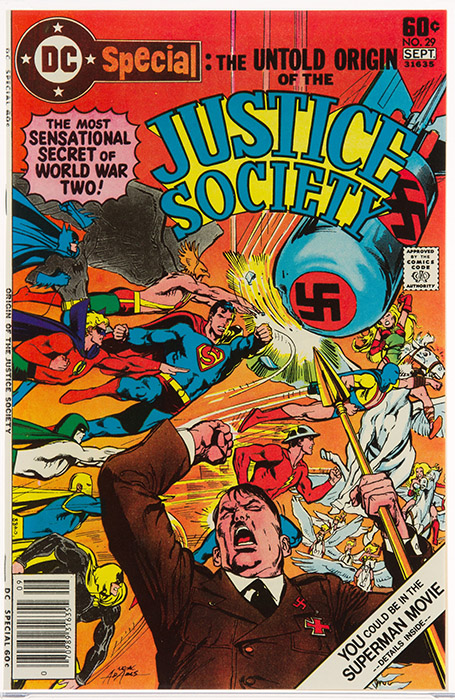

But you know what? That’s okay. No artist wants to keep turning out the same material forever; they’re driven to keep evolving and changing, and there’s always the risk of alienating some of the audience along the way. But no matter: Neal Adams’ place in comics history, and my own life, is forever secure. Over the course of his career, he raised the standards for comics art, shaking up the status quo and opening doors for more young talents with their own innovative ideas. For good or ill, he pretty much invented the notion of the “superstar comic artist” and inspired generations to take their own shot at glory, including a good number who achieved it. Behind the scenes, he championed the cause of creators’ rights and moved the industry forward in terms of fair wages, royalties and health care for writers and artists, most famously shaming Warner Bros into finally doing right by Superman creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster after decades of raw deals.

On a personal level, he turned my passing interest in that Superman character I’d seen on TV into a lifelong love affair with comics of many genres, shapes and sizes, and inspired countless blissful hours sketching out my own dreamed-up adventures on notepads, sketchbooks, paper bags, napkins, church bulletins, newspaper margins and the backs of old printed reports, exams, letters, you name it.

Even now, every time I put pencil to paper, some part of me still harbors a hope that what comes out of my fingertips could rival a Neal Adams creation; after all, that’s how it looks when it starts in my head. Somewhere between brain and paper it all falls apart, but it’s still fun to dream. And for as long as my old peepers function, I can go back and enjoy staring contentedly at those old stories that first pulled me into a universe of imagination and wonder, back when I knew with utter confidence that Neal Adams was the Greatest Artist In The World.

Rest in peace, Mr Adams. Thanks for making my world look so much cooler.