LINKS

- Attack of the 50-Year-Old Comics

- Super-Team Family: The Lost Issues

- Mark Evanier's Blog

- Plaid Stallions

- Star Trek Fact Check

- The Suits of James Bond

- Wild About Harry (Houdini)

Well, I guess it happens to all of us sooner or later (if we’re lucky): this is the year I hit the big 5-0. No doubt the AARP literature is already on its way to my mailbox.

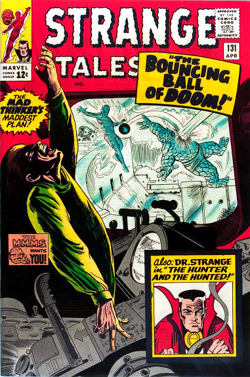

Rather than count the lines on my face and the gray hairs on my head, I figured it might be more fun to examine other things hitting 50 this year, and since comics are never far from my mind, they’d seem as good a place to start as any. This month, I’ll look at Strange Tales #131, bearing an April cover date but actually on newsstands in January, 1965.

Rather than count the lines on my face and the gray hairs on my head, I figured it might be more fun to examine other things hitting 50 this year, and since comics are never far from my mind, they’d seem as good a place to start as any. This month, I’ll look at Strange Tales #131, bearing an April cover date but actually on newsstands in January, 1965.

The official “star” of the book is the Human Torch, who as the presumed fan-favorite member of the Fantastic Four had been spun off into his own feature. Soon enough and for decades to come, he’d be overshadowed by the actual fan-favorite, his team-mate Benjamin J. Grimm, aka the Thing. On the cover of this issue, Ben and Johnny take on the awesome evil of…The Mad Thinker?

Trust your instincts, it’s about as boring as it sounds. Frankly, the Torch’s strip was pedestrian at best and not my area of interest here (In a few months, it’d be shelved to make way for superspy Nick Fury). However, relegated to the back of the book was the infinitely superior Dr. Strange, which is where I’m focusing my attentions today.

As Master of the Mystic Arts, Stephen Strange straddled the divide between Strange Tales’ origins as a showcase for tales of the supernatural and its later transition to superheroics. Decked out in primary hues and constantly moving from frying pan to fire, Dr. Strange checked off several of the requisites for the superhero genre, but there was much more at work here than your typical spandex-clad fisticuffs; this strip owed just as much to H.P. Lovecraft’s pulps, German expressionist films and, visually, the paintings of Salvadore Dali.

As primarily a DC kid, I never totally warmed to the “feet of clay” heroes at Marvel, but Dr Strange was the exception. Originally a supremely gifted but utterly heartless surgeon, Strange suffered an accident that stripped him of his surgical skills and personal fortune and reduced him to a wandering bum in search of a miracle cure. What he eventually found was a new sense of purpose and calling that completely reversed his entire personality, turning him into a selfless servant of humanity. It was a powerful story of redemption and personal transformation and one of my favorite origins of all time. My only regret is that when they finally get around to the Dr Strange movie, they’ll find all that good stuff’s already been strip-mined by other superhero films: arrogant, egocentric jerk gets in touch with his inner hero (Iron Man, Green Lantern, Green Hornet) after an arduous quest to Tibet (Batman Begins), etc. But Dr Strange did it best.

In this particular issue, Strange is on the run from his old nemesis Baron Mordo, who has somehow amped up his own sorcerous powers to incredible new levels (we will learn that he’s being lent power from the far more formidable Dread Dormammu) and has dispatched an army of unearthly wraiths and human spies to scour the globe in search of our hero and their mutual teacher, the Ancient One.

This storyline runs for several issues and remains one of my favorites despite, or maybe because of the fact that the usual formula is shaken up. Strange’s awesome costume — his scarlet cloak of levitation, blue tunic and mystical amulet the Eye of Agamotto — are AWOL as Strange disguises himself in a blue suit and hat, while the Dali-esque vistas of alien dimensions give way to the Earthly streets of Hong Kong. Strange himself, vastly outnumbered and not even sure exactly what it is he’s up against, is strictly on the defensive throughout, surviving by his wits and cunning.

When human spies spot our hero, the extra-dimensional wraiths ramp up the search in Hong Kong, passing through walls and floors, ships and cars while mere mortals carry on their everyday lives, oblivious to the drama unfolding around them.

One of the recurring themes through the Dr Strange strip — at least in these early Stan Lee and Steve Ditko days — is that the forces of magical evil are around us all the time, with only the courage and skill of Stephen Strange standing between us and a fate too horrible to imagine. In fact, it’s often not entirely clear whether menaces are literally invisible or whether they’re so bizarre and mind-blowing that our brains simply refuse to register them. Anyway, the neat part is that Strange is fighting this war under our noses, and never looking for thanks or recognition. Indeed, on the few occasions when people do twig to what’s going on, he’s sure to wipe their memory of the whole episode. This was one of the appeals of old spy movies for me — the idea that high-stakes battles are being fought all around us without us noticing — and here it serves to underscore Strange’s personal transformation from a selfish lout who prizes personal rewards and recognition over charity and compassion, into a selfless messiah who labors on humanity’s behalf without thought of reward. In fact, many regard him as “that magician kook in Greenwich Village”…and that’s fine with him.

This is an aspect I’d love to see explored in the Dr Strange movie: spectacular action scenes unfolding around (and through!) unsuspecting bystanders, and a complete lack of acknowledgement from the public that he’s done anything at all. At the very least, I don’t want to see Avengers-style mayhem with folks running in panic as giant demons knock over buildings and stomp cars. That would be missing the whole point.

Arguably the most memorable visual in this story comes as Strange is making his getaway on a passenger jet and one of Mordo’s spies discovers him (hey, “Wraiths On A Plane!”). Like air travel doesn’t make me nervous enough, already.

Here we get a (colorless) glimpse of Strange’s normal costume as his astral self separates from his physical body to do battle with the wraith. This was a common stunt in the Ditko days, and it’s interesting that his “magic suit” has a “spirit” while his street duds do not. Logically it would just be Strange himself who has an astral self (not his clothes), but you couldn’t exactly have a naked hero floating around in a 1965 comic. Anyway, banishing (destroying?) the wraith, Strange, still in astral form, realizes he wouldn’t look all that different from the other wraiths with a slight change to his costume, so he disguises himself as a baddie and waves off the others, allowing him to escape on the plane.

And so our hero lives to fight another day. The serial has a couple more installments to go, but that’s all we get here in January, 1965. Not that I’m complaining: there’s more packed into these ten pages than you’d get in three issues of a modern comic.

Verdict? Stephen Strange is still looking awesome 50 years on, with just a dash of gray at the temples and despite that pencil-thin, Ronald Coleman mustache that was already two decades out of date in 1965. Off and on, other writers and artists would treat Strange and his fans to other awesome adventures, but on the whole he never topped his glory days at the hands of Stan and Steve. I’m looking forward to seeing what Marvel can do with the guy on screen. Casting Benedict Cumberbatch was a good first step; he can do heroic, he can do “selfish egomaniac” and he’s probably got the best voice in the biz for uttering phrases like “By the Hoary Hosts of Hoggoth!”

Great to read some praise of early Dr Strange. When I was 12, my aunt gave me a collected edition of the first eighteen stories. Up till that point I’d seen nothing like it (or hadn’t noticed anything like it). I never thought of Dr Strange as a super-hero. I sensed it was all part of a different genre. Maybe I was wrong. Anyway, I loved those comics and still do. One thing that really intrigued me was that Strange wasn’t inherently magic; he LEARNED magic, the way a student learns martial arts from a kung-fu master. This was quite an exciting idea for me. (Perhaps if I, too, climbed the right mountain, and knelt at the feet of the right master, I could do all of these amazing things as well.) There’s something I love about a redemptive story like Strange’s, in which the master recognises the hidden potential of his flawed pupil. Green Lantern had a similar “it could be me” element to the story, except for the bald fact that Hal was already honest and born without fear… What poor 12-year-old can imagine himself to be “born without fear”?? Speaking of the Torch, I suppose Marvel figured he ought to have been the natural idol of the teenage demographic; however, he was no Spider-Man, obviously. Some characters are awesome within their original group, but are very unappealing outside of it (I could mention Wolverine here). I like your “old spy movie” parallel… Lee and Ditko deserve much credit for actually making us care about what happens to these secret-realm characters.

I think the reasoning was “The Torch was a huge sensation in the Golden Age, so he’s a sure bet, now.” The difference, though, was that the original Torch fulfilled the violent potential of a character based on fire, with lethal results, whereas the the Silver Age version was decidedly more Code-friendly. And if Timely Comics appealed to fantasies of empowerment (and retribution against bullies…like Hitler), the Marvel Age was more about making heroes from loners, outsiders and social misfits…of which the Thing was a much better example.

You make a great point about Strange *achieving* his powers instead of inheriting them. Superman was born with both mighty muscles and noble spirit. Spidey had “great power” dropped in his lap and spent the next 50 years complaining about it. Captain America was a paragon of virtue from the cradle on, but needed that injection to give him the strength to make a difference. But Stephen Strange was a bust as a human being; his transformation was total. He had to work for his powers, and that meant more than just years of instruction and practice; it also meant letting go of all his hang-ups and remaking himself from the ground up. Anyone who works for something that hard is not likely to sit around moping about getting it. Maybe that’s why I liked him so much; unlike DC heroes, he wasn’t automatically virtuous and heroic by birth, but unlike Marvel characters he didn’t see his powers and responsibilities as a burden. He was, basically, a jerk who got his act together and turned his life around.

I may have had the same book you did as a kid: it was a mass-market paperback collection (pocket-size). There were two volumes and I still cherish them both. And I agree part of the appeal was the “otherness” of it. I’ve always complained that comics are “all superhero, all the time” but the reality is I always picked superhero comics over other genres, so I’m part of the problem. Dr Strange was as close as you could get to superheroes and still claim you were reading something “different” so he was perfect for me.