LINKS

- Attack of the 50-Year-Old Comics

- Super-Team Family: The Lost Issues

- Mark Evanier's Blog

- Plaid Stallions

- Star Trek Fact Check

- The Suits of James Bond

- Wild About Harry (Houdini)

It’s likely the first images I ever saw of Batman were created by Carmine Infantino. Sometimes I try to remember my first exposure to the character and I’ve just about decided it wasn’t through the comics, the TV show or cartoons, but through the merchandising. By the time I was old enough to toddle around, the live-action TV show was winding down, but the tidal wave of related toys, lunchboxes, trading cards and sundry other gee-gaws it had inspired was, if not still cresting, then leaving the shores thoroughly littered with bat-this-and-that’s as it receded. And a lot of that material featured imagery created by Mr Infantino, who passed away this week at 87.

When he was roped into re-vamping Batman in 1964, Infantino had already played a key role in launching comics’ “Silver Age,” having re-introduced The Flash with a deceptively simple-looking costume that broke with “cape-and-shorts” tradition and actually looked like something a guy could comfortably run in. His fluid designs, nimble figures, space-age skylines and dynamic layouts were about as far as you could get from the stiff, flat, lantern-jawed take on Batman that Bob Kane’s ghosts had been churning out for decades, and considering the Caped Crusader’s sales were in the toilet, just the shot in the arm he needed.

When he was roped into re-vamping Batman in 1964, Infantino had already played a key role in launching comics’ “Silver Age,” having re-introduced The Flash with a deceptively simple-looking costume that broke with “cape-and-shorts” tradition and actually looked like something a guy could comfortably run in. His fluid designs, nimble figures, space-age skylines and dynamic layouts were about as far as you could get from the stiff, flat, lantern-jawed take on Batman that Bob Kane’s ghosts had been churning out for decades, and considering the Caped Crusader’s sales were in the toilet, just the shot in the arm he needed.

It’s probably hard for modern Bat-fans to appreciate how huge a deal the shift in art styles was back in 1964. Batman has attracted so many stellar artists for so long that it’s easy to forget he was locked in one art style for an incredibly long period, and that that style could most charitably be described as “primitive.” Infantino’s comparatively realistic and far more contemporary style — known then and now as “New Look” Batman — was such a jolt it sent fans into two camps; those more than ready for a change and those who thought Batman, like Dick Tracy, could only be drawn properly by his creator (a debate that played out in the pages of fan magazine “Bat-Mania” which, if you’re off a mind, can be downloaded for free here). It was in that same forum that fans would soon learn Batman’s “creator” had in fact not drawn the strip in years, and may not even have been the “creator” at all, but that’s another story.

The point is, Infantino helped give the character the boost he needed to reverse his sales slump and get him back on the map with readers, which in turn led to the TV show, followed by a cartoon series that used Infantino’s designs, and all that groovy bat-gear.

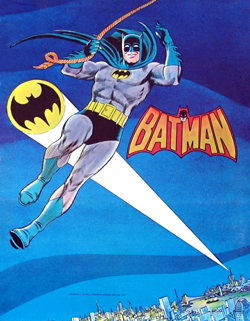

As I get older, it gets ever harder for images to stick in my mind, but certain ones from early childhood remain as vivid now as they were the first time I saw them: Oddjob throwing his bowler hat, the Beatles in their Yellow Submarine, Steve Austin running in slow-motion, and comic images like the one below, created as a pin-up by Carmine Infantino and recycled endlessly on posters, album covers, statues and the cover to one of the most-prized books in my collection, “Batman From the 30s to the 70s,” not to mentioned being, along with the covers to Action Comics #1 and Spider-Man #1, one of the most imitated, parodied and plain old ripped-off comic book images of all time:

Then there was the “arms akimbo” pose that was used on tons of merchandise, including a version that was embossed on the bottom of everyone’s favorite die-cast vehicle toy, the Corgi Batmobile:

Infantino’s pin-ups of Batman villains the Joker, the Penguin and the Riddler were, likewise, the definitive images of those characters for a generation:

None of which is to imply that Infantino’s career began and ended with Batman. He was one of the few talents to be around almost from the beginning and stick with it for decades, starting in the “Golden Age” of the 40s by introducing the Black Canary, evolving his style through the 50s with work on fantasy, sci-fi, adventure and Western strips and in 1956, as noted, ushering in a second era of superhero dominance with the re-imagined Flash. As the 60s gave way to the 70s, he took the unusual post of “cover editor,” drawing roughs for the covers of almost all of DC’s titles and establishing a “house style” to be followed by such luminaries as Nick Cardy, Neal Adams and Murphy Anderson. In the early 70s, with DC more or less on the ropes as Marvel Comics dominated the field, Infantino became the first artist ever to serve as Publisher of a major comics line, hiring on a new generation of artistic talents and creating an atmosphere of creative freedom that eventually wooed even Jack Kirby away from Marvel. In short, he created “my” DC, the comics I started with and which inspired a lifelong interest. More recently, reprints of his Silver Age work on The Flash and Adam Strange have made a comics fan of my son, Jason.

Of course the down side to being a constantly evolving artist is that sometimes you evolve too far for your audience, and as Infantino’s art became more and more stylized and quirky, he left a lot of readers behind, including yours truly. By the late 70s and early 80s, I started actively avoiding his work on titles like Star Wars because it was just too angular and cartoony for my tastes. Back on The Flash again in the 80s, he drew what seemed to me an utterly interminable storyline called “The Trial of The Flash,” which between lasting literally for years and featuring that ever-more oddball art style pretty much led to the character being killed off in 1986’s “Crisis on Infinite Earths.”

And so he became a sort of poster boy for the cycle that defines all truly innovative artists with an individual style and a desire to keep growing; you start off with folks calling you an “exciting young talent,” progress if you’re lucky to “genius” and “giant in the field” and end up with “meh, I liked your old stuff better.” But oh, that old stuff!

I was lucky enough to meet Mr Infantino at a late 90s convention and got him to sign, among other things, a poster of that “rooftop” image, which was pretty awesome. He seemed like a nice guy, if a bit tired, but then I’m guessing he had that image shoved in front of him about a zillion times over the years. To him, it was old news, one of countless jobs he cranked out in a long career, if for some reason just more popular than a lot of the others. But to me, it was one of the most powerful images of childhood, one that unlocked a whole universe of imagery and adventures and a lifetime love of comics.

I’ve often thought it must be awesome to connect, really connect with an audience on a meaningful level, whether through a portrayal, a song, an artwork or whatever. I hope Mr Infantino knew that he made that kind of connection with a lot of readers. Either way, he’ll live on through his work, and that’s not a bad legacy to have.

Great article. He will always mean a lot to me as the artist on Flash comics, which I loved, and also of course Adam Strange. I remember him always being paired with good, solid inkers. (Even in that poster you love, Murphy Anderson’s contribution is very strong.) No Flash moved like his Flash.

I had no idea he had passed away till I saw your post here.